Fatal Police Shootings Of Unarmed Black People Reveal Troubling Patterns

Enlarge this image

Demonstrators raise their arms and chant, «Hands up, don’t shoot» on Aug. 17, 2014, as they protest the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo.

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Joe Raedle/Getty Images

Enlarge this image

Ronell Foster was fatally shot by Vallejo, Ca., police officer Ryan McMahon in 2018 after being stopped for riding his bicycle without a light. Foster was unarmed.

Foster family

hide caption

toggle caption

Foster family

Enlarge this image

Charmaine Edwards (left) speaks to supporters during a protest outside a courthouse in Dallas in 2017. Jordan Edwards was a 15-year-old in Balch Springs, Texas, when he was shot and killed by police.

LM Otero/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

LM Otero/AP

Enlarge this image

Nathaniel Pickett II (right), who suffered from mental illness, was shot to death by a San Bernardino County, Ca., sheriff’s deputy in 2015 after he was stopped while walking to the motel where he lived. Pickett was unarmed. His father (left) and mother sued the county and were awarded $33.5 million.

Nathaniel Pickett Sr.

hide caption

toggle caption

Nathaniel Pickett Sr.

Race

In 2020, Protests Spread Across The Globe With A Similar Message: Black Lives Matter

Hidden Brain

The Air We Breathe: Implicit Bias And Police Shootings

Nathaniel Pickett Sr., 65, said that Nate was the only child he had with Dominic Archibald, a two-time combat veteran and retired Army colonel. After their divorce in 1990 when Nate was not quite 5, the boy went to live with his mom. He became a Boy Scout and fancied Frank Sinatra music, art and sports—except football because he didn’t like getting dirty. Archibald eventually enrolled him at the Fork Union Military Academy, an all-boys college preparatory boarding school in Virginia. She agreed to let him transfer in his senior year to Woodrow Wilson High School, a public school in Washington, DC.

«We just wanted him to be happy,» Pickett said.

Less than three years after Pickett’s death, Woods was involved in a second on-duty shooting of another unarmed man.

Minutes after starting his 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. shift on Jan. 14, 2018, Woods noticed the man, Ryan Martinez, driving his black Jeep in Barstow without an illuminated license plate. He activated his lights and siren, and hit the gas. During the pursuit, Martinez lost control of the car and ran off the road into a drainage ditch, police records show. The car flipped. Woods said he ordered Martinez to show his hands. He refused. Woods fired two shots at him but missed. Afraid that Martinez might have a gun, Woods tasered him unsuccessfully before drive stunning him in his leg. Woods then shot him in the chest and hand when he said the man «reached for his waistband area.» Martinez, 27, survived. No gun was found at the scene, according to police records.

Woods was not wearing a body camera. Martinez did not respond to a request through his mother for an interview.

«He was shot 3 time [sic],» his mother, Kathy Searcy said in a Facebook message to NPR that included photos of his bullet wounds. «Plus, he was being tased at the same time.»

Michael Ramos, the San Bernardino County district attorney at the time of both shootings, declined to charge Woods, saying Woods was justified in shooting both men. He said in a recent phone interview with NPR that he doesn’t remember the cases, but said he always adhered to the law when deciding whether to charge an officer with killing someone.

Enlarge this image

San Bernardino District Attorney Michael Ramos speaks during a press conference in 2018. In an interview with NPR, the now former DA defended police officers, saying that they have an impossible job.

Stan Lim/The Press-Enterprise Group via Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Stan Lim/The Press-Enterprise Group via Getty Images

Code Switch

A Decade Of Watching Black People Die

Code Switch

How Segregation Shapes Fatal Police Violence

Of seven officers charged with manslaughter, two were found guilty.

In 33 shootings, officers were fired or resigned. At least three got their jobs back and five went on to work for other law enforcement agencies, records show.

Philip Stinson, a criminal justice professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio and former police officer in Virginia and New Hampshire, said it’s difficult to prosecute cops charged with murder or manslaughter from an on-duty shooting because juries often sympathize with them.

«The courts are very reluctant to second guess the split-second decisions of police officers in potentially violent street encounters that might be life or death situations,» Stinson said. «They somehow seem to take everything that’s been presented in the case, in the trial, and just disregard the legal standard.»

Ronald C. Machen Jr., the U.S. attorney for Washington, DC for more than five years during the Obama administration, said that prosecuting police officers who gun down unarmed Black men and women will continue to be challenging until there are more «minorities in the system.»

«This is why you need Black prosecutors and Blacks on juries — to hold people accountable,» Machen said. «For police officers to have the credibility to do their jobs, they have to be held accountable.»

One cop, five shootings

The decision to not hold officers accountable doesn’t rest solely with prosecutors. Police unions often make it all but impossible to remove an officer from the force, despite repeated shootings and other infractions.

Jerold Blanding was involved in five shootings—two off duty and three on duty—during his 24-year career with the Detroit Police Department, a review of more than 1,700 pages of agency records shows. One was fatal. He also shot a pigeon and was investigated for assaults on police officers, improper conduct, harassment, excessive use of force, domestic violence and threats. Yet he kept his job.

Known for having a temper, Blanding’s troubles started three years after his March 1994 hiring, when he shot a man while off duty at a Detroit nightclub, police records show. The victim survived. A year later, he was involved in another off-duty, non-fatal shooting at an ATM, after a man who was confused mistakenly tried to get into Blanding’s car. Blanding was exonerated in both incidents.

Enlarge this image

Jerold Blanding was involved in five shootings—two off duty and three on duty—during his 24-year career with the Detroit Police Department, agency records show. One was fatal.

Michigan Department of Corrections

hide caption

toggle caption

Michigan Department of Corrections

Enlarge this image

Former Kingsland, Ga., police Officer Zechariah Presley was found not guilty of manslaughter in the 2018 shooting death of Anthony Green, who was Black and unarmed. The officer was hired on the force despite numerous «red flags,» including assault and a rejection from another police department in a neighboring town.

Kingsland Police Department via AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Kingsland Police Department via AP

Enlarge this image

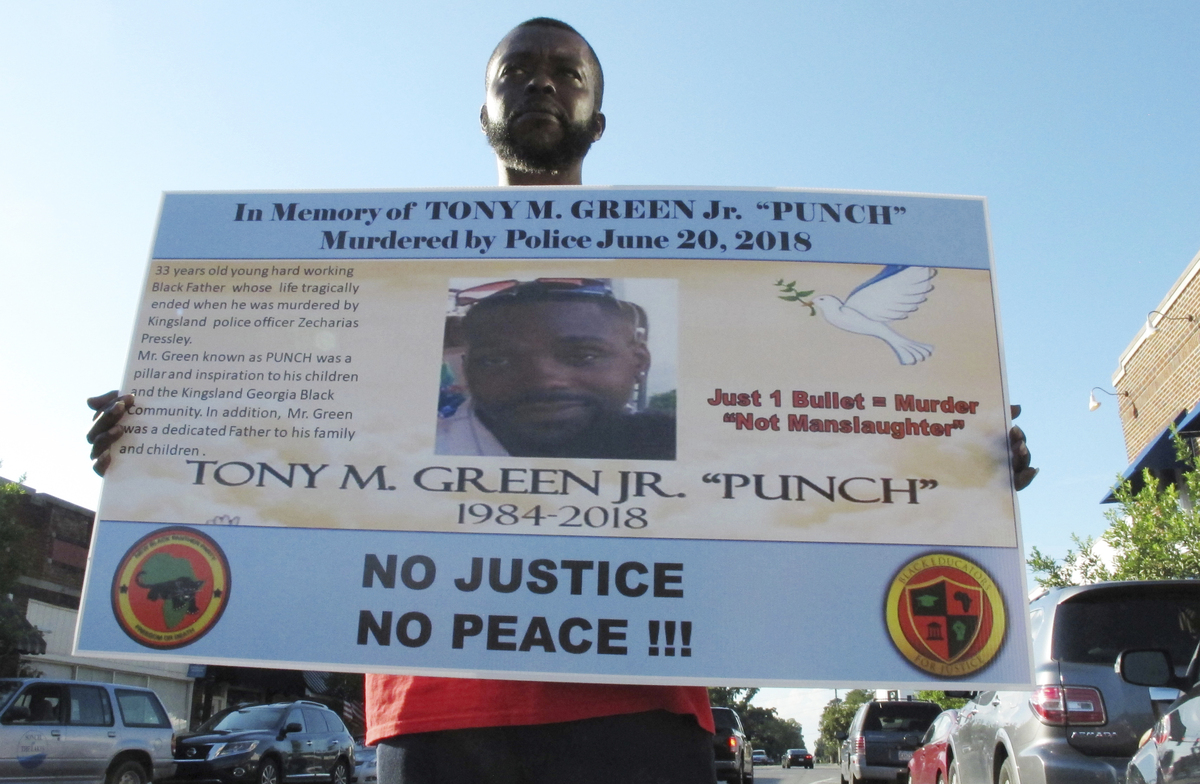

Tony White holds a sign showing a photograph of his slain cousin, Tony Green, outside Kingsland City Hall in Kingsland, Ga. Authorities say Green was fatally shot in 2018, while he fled Kingsland police officer Zechariah Presley.

Russ Bynum/AP

hide caption

toggle caption

Russ Bynum/AP

Tony White holds a sign showing a photograph of his slain cousin, Tony Green, outside Kingsland City Hall in Kingsland, Ga. Authorities say Green was fatally shot in 2018, while he fled Kingsland police officer Zechariah Presley.

Russ Bynum/AP

Jones and others acknowledged that departments often hire officers like Presley because they’re desperate to recruit and are willing to ignore red flags.

«We need bodies,» Jones said. «Some places have been willing to lower the standards and bring bodies in, and it’s a recipe for disaster.»

Rosenfeld said that departments, mostly small ones that lack resources, are «more willing to look past misdeeds.»

«Small departments that are strapped for officers take them where they can find them,» he said.

Green’s death has prompted changes in the department, including mental health treatment for officers and a hiring board to review candidates, Jones said.

«It’s more important for us to move forward, train properly and to show that the stigma of what happened with Presley will not be tolerated,» he said.

LaMaurice Gardner, a police psychologist in Detroit, said the toll that one shooting—or more—takes on a police officer can be devastating.

«People don’t realize the psychological effects a shooting takes on an officer and their family,» said Gardner, who has worked as a reserve officer for 26 years in suburban Detroit. «You’re investigated like you’re a perpetrator. You can’t work on the street. You can’t get overtime. Your peer support is pulled away.»

Gardner acknowledged that departments face difficult issues now with police shootings, including of unarmed Black men and women..

«Are there bad cops out there? Hell, yeah, there are,» he said. «Policies need to be changed.»

NPR’s Emine Yücel contributed to this story.

Комментарии 0