Iraqi Family Identifies Their Son As ISIS Teen At Center Of Navy War Crimes Trial

Enlarge this image

Jamal Abdullah Naser watches a video of a teenager he says is his son, Khaled Jamal Abdullah, just before he died in custody of the Navy SEAL. The young fighter was captured after an airstrike near Mosul and was killed by a Navy SEAL medic who was treating him. Naser was never told what had happened to his son.

Jane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jane Arraf/NPR

Enlarge this image

Navy Special Operations Chief Edward Gallagher walks out of military court with his wife Andrea Gallagher, during court recess on July 2, 2019, in San Diego, Calif. He was pardoned by President Trump after being convicted of posing with a teenage ISIS captive’s body. He was acquitted of murder.

Sandy Huffaker/Getty Images

hide caption

toggle caption

Sandy Huffaker/Getty Images

Enlarge this image

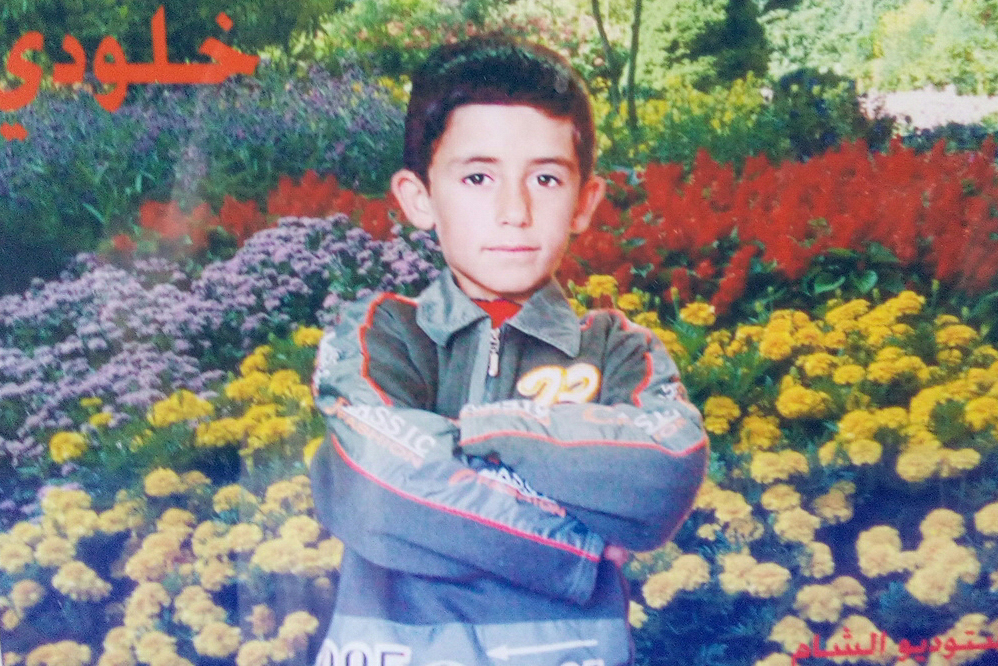

Khaled Jamal Abdullah after running away from home to pledge allegiance to ISIS and join them as a fighter. He had just turned 16.

Jamal Abdullah Naser

hide caption

toggle caption

Jamal Abdullah Naser

Enlarge this image

Fawzia Ahmed, along with her daughter and grandson, watches for the first time an Iraqi television interview with her wounded and captured son Khaled, on the day he was killed by a U.S. Navy SEAL.

Jane Arraf/NPR

hide caption

toggle caption

Jane Arraf/NPR

Enlarge this image

Khaled Jamal Abdullah, a month after turning 6.

Jamal Abdullah Naser

hide caption

toggle caption

Jamal Abdullah Naser

Khaled Jamal Abdullah, a month after turning 6.

Jamal Abdullah Naser

When Khaled pledged allegiance to ISIS in 2016, the militants had controlled Mosul for two years and the U.S. and Iraqi military had started the fight that would lead them to liberate the city. For being a fighter, ISIS paid him $50 a month, his father says.

«He joined at the end of the Islamic State — in the last days,» says Naser. «I told him, ‘Why are you joining? Look, ISIS is running away from the troops. What are you going to do against the planes and U.S. technology and all those countries?'»

His father promised to buy him a motorbike if he didn’t leave. He told him joining would destroy him and the entire family. When Khaled insisted, Naser took away his ID, thinking if he didn’t have it, he couldn’t join. Naser confirms that he did even hit him to try to force him to stay home.

«After he joined, they took him for a month to train him,» Naser says. «When he came back he said, ‘Dad,’ and started crying. He was a child. He said, ‘I can’t quit. If I quit, they will punish me.'»

In the roughly 10 months he spent with ISIS, he came home twice to recover from being wounded before he was injured the final time, his father says.

Then, in late 2016, as U.S. and Iraqi forces moved in, ISIS forced the family to move to Mosul as human shields. The police and the mayor’s office in Shoura say Naser is known as an honorable man and not an ISIS supporter. But after Iraqi forces took back their neighborhood in Mosul in May, 2017, Naser and his family were moved to an Iraqi detention camp where relatives of ISIS fighters were held. To be able to return home under tribal rules, Naser agreed to legally disown his son.

Khaled’s parents say they had never heard of the Gallagher trial. U.S. investigators spent weeks in Iraq gathering evidence for the investigation. But Naser says no one ever contacted the family of the victim at the center of it.

The U.S. military has not responded to NPR questions about why the family was not informed.

The location of the teenager’s body is unknown. The Iraqi commander interviewed by Navy investigators said he was left dead on the ground.

More than a year after Mosul was declared liberated in July 2017, NPR saw bodies of fighters amid building rubble as civilians returned. The Iraqi government and military eventually collected the bodies and dumped them in a mass grave.

When NPR tells Khaled’s parents about the trial in the U.S. and that a Navy SEAL confessed to killing Khaled, they are shocked. International law considers killing or wounding combatants who are unable to defend themselves as a war crime.

«It’s true Khaled was a criminal but he was a prisoner,» says Naser. «America has civilization and development and humanity. Why did they do this? He should have been taken to court and the court would have sentenced him. He was 17. He was a child.»

«It is a murder,» Naser says. «We consider that they murdered him.»

The town Khaled came from, notorious for the numerous ISIS fighters from there, is a collection of mostly unpainted concrete houses surrounded by the stubble of fallow wheat fields. A sulfur factory that used to employ townspeople is now shut. It’s a poor community and, like many in Sunni areas, is alienated from the Shiite-led central government by years of neglect.

Local police commander Col. Adhal Dhiab Aziz says three-quarters of the young people in town joined ISIS.

Aziz leafs through a yellow file folder of printed and hand-written pages listing residents who joined ISIS. There are 33 pages with more than 2,500 names — about a quarter of the town’s entire population — and he is still adding to them. Among them are long columns of young men named Khaled. He flips through the pages until he finds Khaled Jamal Abdullah.

«All of the people here pledged allegiance to ISIS,» he says. «Some are dead, some are alive, others are hiding in the desert, some others are in jail.»

And one ended up the unknown victim in a U.S. war crimes trial.

- Special Operations Chief Eddie Gallagher

- Eddie Gallagher

- Edward Gallagher

- Islamic State

- ISIS

- Iraq

Комментарии 0